- calendar_month October 4, 2023

- folder Topics

Credit to: Seth Styles JohnHart Real Estate

Featured image credit: Visitor7

We often talk about the history of Los Angeles on this blog, but today we’re going back to the very beginning. Sort of. Indigenous people lived in the area we call Los Angeles for centuries before the city’s first stone was laid. But if you ask locals to take you to the beginning, most will guide you to a vibrant pocket at the border of Downtown LA called Olvera Street. You may have also heard of this storied pedestrian street under its Spanish name, Calle Olvera. Here you’ll find some of the oldest surviving buildings in the city, along with plenty of kiosks, shops, and restaurants with a decided focus on Mexican culture. Or at least a tourist-approved facsimile of it, depending on who you ask. But the true story of Olvera Street (not to mention El Pueblo de Los Ángeles) began about a block northwest of its current placement.

The Spanish Settlers That (Sort of) Started It All

Under a decree of King Carlos III of Spain, 11 families departed their homeland to found a secular pueblo. Their destination? The sunny frontier of Southern California . These 44 men, women, and children, chaperoned by a handful of Spanish soldiers, eventually set up camp at a fortuitous area bordering what we regard today as the LA River.

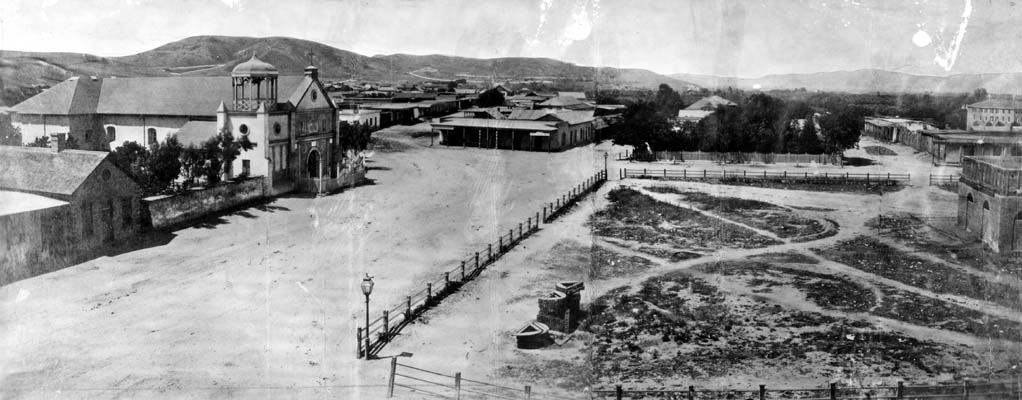

Thus on September 4, 1781, these Spanish settlers founded what they called El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles. What started as a simple settlement quickly grew into a full scale plaza centered around a sub-mission established by priests from the nearby Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. This mission was where the Spanish settlers had stayed en route to what would eventually become El Pueblo de los Ángeles.

Yet, the wind wasn’t exactly at these Spanish settlers’ backs as they tried to grow their pueblo. Erratic flooding hastened general disrepair. Eventually, it became clear that a riverside pueblo was just too unpredictable to properly maintain. Therefore, the settlers picked up stakes and moved sometime between 1815’s great flood and 1835’s establishment of Los Angeles as a proper ciudad. The new location? An area that we know today as Olvera Street.

Olvera Street Before Olvera Street

With the settlers gradually moving southeast to the area that would be present day Olvera Street, it’s impossible to pinpoint an exact date of establishment. Therefore, most historians date the original Olvera Street back to sometime in the 1820s. Back then, no one knew Olvera Street as Olvera Street, nor did it constitute the entire settlement. Rather, it was a small street that branched off from the Plaza de Los Ángeles.

It’s likely that much of the shift from the Spanish settlers’ original location to the new location near the Plaza de Los Ángeles occurred while Spanish rule was transitioning to Mexican Independence. But under Mexican rule, the Plaza de Los Ángeles served as a constant point of community.

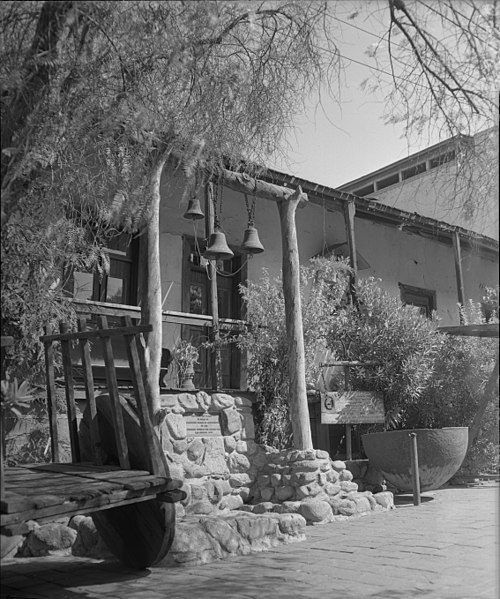

At this point, locals commonly referred to this area as Wine Street or even Vine Street. This was due to the proliferation of grape vines growing in the area, popularly pressed in the making of wine. Around 1855, builders constructed the Pelanconi House, a winery, on what would eventually become Olvera Street to capitalize on the abundant grapes. It remains today as the oldest standing structure in Los Angeles built from fired brick. Unsurprisingly, DNA testing on the grapes (which still grow on Olvera Street to this day) have been shown to match the genetics of grapes growing at Mission San Gabriel, forging an irrefutable link to LA’s initial Spanish settlers.

The Gritty Early Days of an LA Icon

Olvera Street didn’t get the name we recognize today until 1877. The Los Angeles City Council authorized the name change in tribute to the county’s first Superior Court Judge, Agustin Olvera, who had an adobe home in the area. Like so many of the city’s initial structures, Olvera’s adobe home was lost through the decades.

By the time Olvera Street became Olvera Street, it was already suffering from extreme neglect. Yet, it still served as a haven for many Mexican, Sicilian, and Chinese immigrants seeking fresh starts in a new city. Eventually, much of the Chinese population was displaced by the installation of Union Station, serving as the catalyst for the neighborhood we know today as Chinatown. But well into the 1920s, the area surrounding the Plaza de Los Ángeles served as a landing pad for Mexican immigration.

Saving the Ávila Adobe

For better or worse, again depending on who you ask, Olvera Street’s trajectory changed in 1926 when the city’s plans to raze the historic Ávila Adobe grabbed the attention of local widow Christine Sterling. Seemingly dogged by hardship, Sterling escaped into the romance of LA’s past. During one of her many explorations of the city, she’d stumbled upon the Ávila Adobe and fallen in love with its rustic charm, despite its dilapidated state. She was predictably horrified to hear of the city’s plans for one of LA’s oldest abodes.

When Sterling’s complaints to the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce did little to sway the city’s decision, she turned her appeals to Harry Chandler, the publisher of the Los Angeles Times. By this point, Sterling’s concept had evolved well beyond simple preservation of a historically significant building. She now wanted to create a joint marketplace and attraction that promoted what she deemed as the authentic heritage of California.

Yet, Sterling held a highly romanticized concept of California’s Mexican heritage; one that was further amplified by Chandler’s involvement. It was a Disney-fied take on Mexican culture, three decades before Disneyland. Galvanized by the concept, Chandler began to promote Sterling’s efforts through press exposure. People who’d never have noticed the Ávila Adobe were paying attention.

The Community Speaks

It still wasn’t enough to move the city’s needle, and funding for Sterling’s ideas was severely lacking. In November 1928, Sterling arrived at the Ávila Adobe to admire it, only to find an official notice of condemnation posted on the property. Incensed, the budding preservationist responded with her own hand-painted diatribe, ridiculing the city for its failure to protect its own cultural history. And, against all odds, Sterling’s sign was the final push that tipped the balance of public opinion. Reading the room, the LA City Council rescinded the condemnation of the Ávila Adobe. And, thanks to Sterling’s efforts, the home remains standing today as the oldest surviving home in Los Angeles.

Ultimately, it took the cooperation and good will of the entire community to restore the Ávila Adobe. Much of the labor was “donated” by Los Angeles Police Chief James Davis who bussed in prison inmates to handle the hard labor. Despite several businesses pitching in with donated supplies, funds were still dwindling until Chandler intervened. After holding $1,000-a-plate luncheons with high profile corporate donors, he was able to muster the capital needed and then some. It led him to found the for-profit Plaza de Los Angeles Corporation, the organization at the center of so many of the area’s restorative efforts. Sterling remained heavily involved with Olvera Street as we know it today. In 1929, it was limited to a pedestrian street, making it safer for vendors and shoppers alike.

Olvera Street as We Know It

It was Easter Sunday 1930 when the hybrid tourist attraction, historical street, and cultural center Olvera Street opened to the public. Though it was known as Paseo de Los Angeles, it was more popularly referred to as Olvera Street. Eventually, public preference won out. From old-style restaurants serving tourist-approved Mexican cuisine to vendors and shops selling sugar skulls, candles, masks, jewelry and other culturally-steeped souvenirs, Olvera Street seemed to radiate life from the very beginning.

Today, it’s still a tourist hotspot. Some critics have pointed out the hyper-cultural representation of Mexican heritage on display as reductive. It’s more of a caricature of authentic Mexican culture than anything. Ultimately, that decision lies in the heart of the visitor. But if you recognize that Mexican culture runs much deeper than Catrina dolls and churros, Olvera Street offers a great way to support small businesses while enjoying a sunny afternoon in LA.